A first-world country with a disgraceful domestic and family violence problem. A developing Latin American nation with a unique model for policing it. And, a world-first study by a multi-national team of university researchers, asking the question: Can Argentina’s female-led police stations teach Australia and the western world how to better respond to, and prevent, gender-based violence?

The Problem

Every week, in Australia, one woman is murdered on average.

Far too often, the violence that women, and children, experience at the hands of their male partner dominates Australia’s news headlines.

Like most developed nations, Australia rightfully recognises and prosecutes gender violence as a crime, meaning it's dealt with by traditional policing and judiciary systems.

But, is there a better way to respond to, and prevent it?

Criminologist Dr Kerry Carrington, an Adjunct Professor of the University of the Sunshine Coast, believes there is.

To explore these alternative strategies, we travel to Latin America where women-led police stations are impacting access to safety for female victims of male violence.

Welcome to the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

So. When those committing the crimes are the ones meant to protect and serve. When the perpetrators of injustice are meant to prevent it, how can trust in government, in police, ever truly be restored?

The Setting

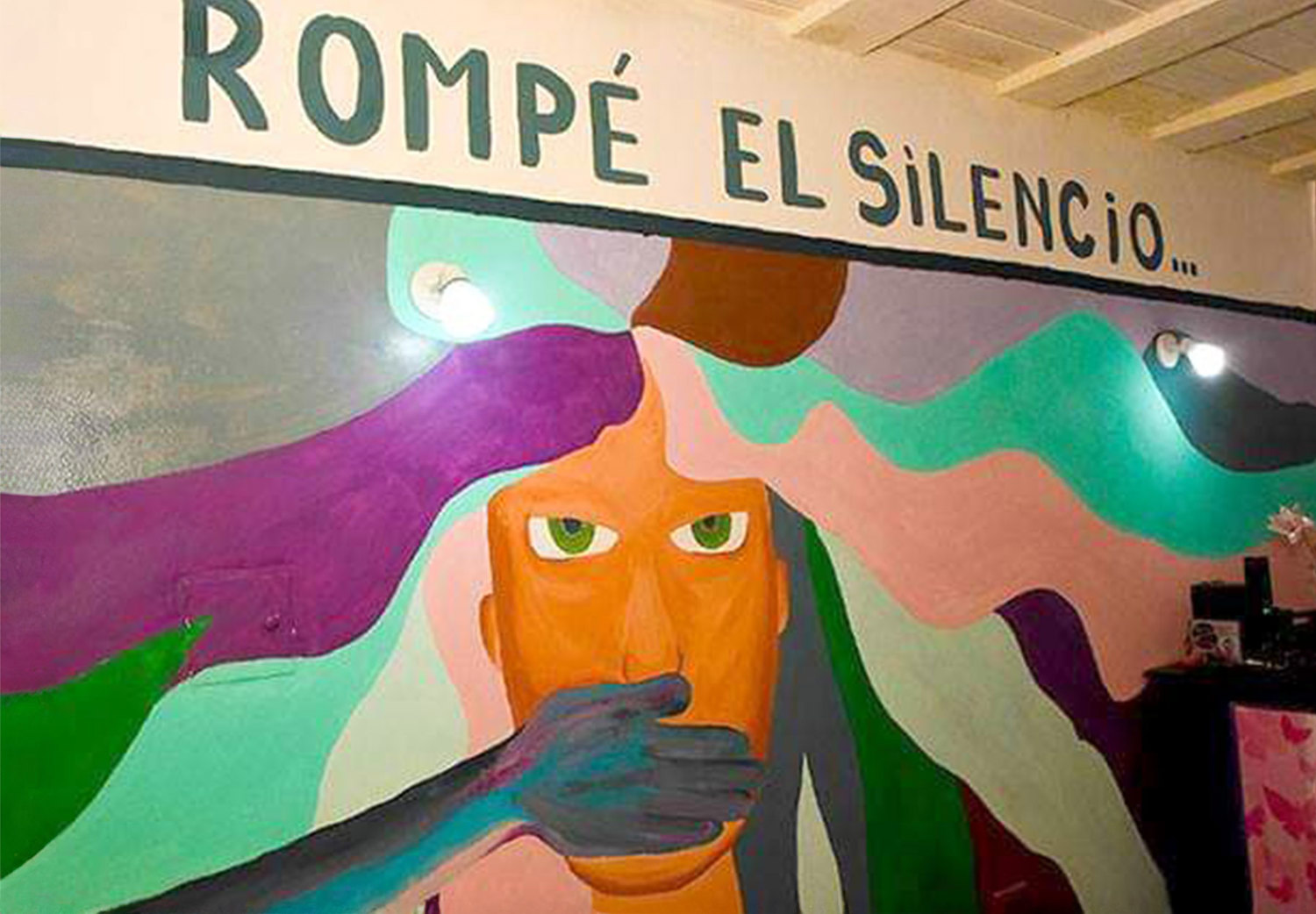

Rompe El Silencio. Break the Silence.

Three powerful words in giant letters form part of a bold mural painted across the entrance to a police station in Argentina.

The mural is impossible to miss. It is a beacon for victims of gender-based violence, showing them where they can seek help, pointing the way to a safe-haven for them and their children. The mural has been painted by a group of survivors, as part of their therapy.

“Yo te creo,” I believe you. “Ni una menos,” not one more. “No al violencia,” no to violence. Huge murals with these messages adorn specialist police stations across Argentina’s barrios, primarily in town districts with high levels of poverty.

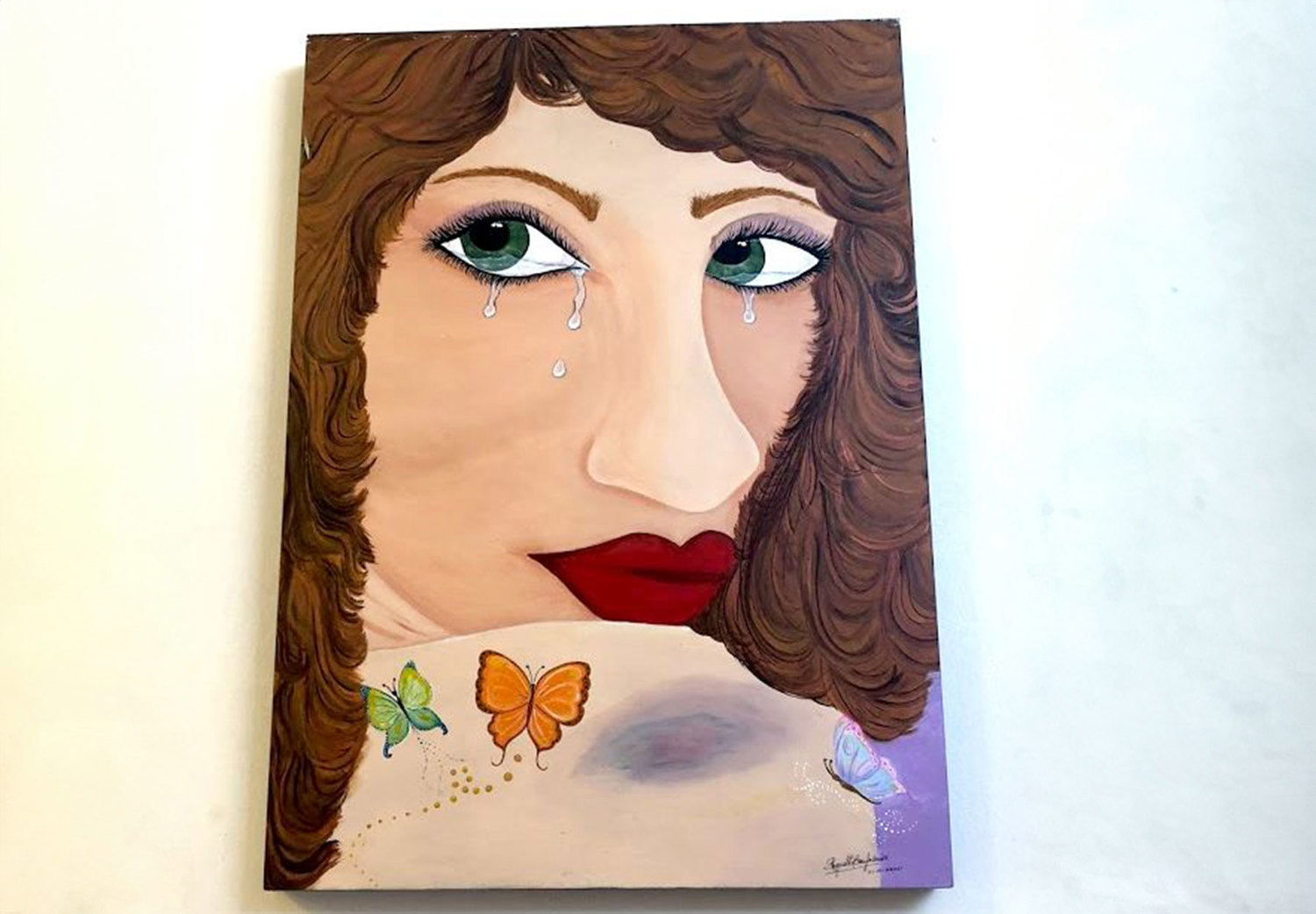

Butterflies, too, are painted everywhere, a symbol of freedom from violence. Butterflies are the mascot for these specialist police stations, which are unlike ordinary police stations in both purpose and appearance.

Argentina has two types of policing, each with their own command structure and reporting to their own commissioner. The ‘Comisaría’ or common police that perform regular policing duties, and the ‘Comisaría de la Mujer y la Familia (CMF)’ which are specialist police for women and families.

Like traditional policing models, the specialist stations offer a 365-day emergency response service, wear police uniforms and weapons, have the authority of the state, and the same powers and training as general police.

Unlike regular police stations, specialist stations look nothing like the traditional justice-serving hubs where the peace is upheld via locks and keys and handcuffs and impenetrable, sterile walls.

There are no holding cells, as they are not designed to receive alleged offenders. They are designed solely to receive victims and their children.

Police are vetted from criminalising victims seeking help. They don't investigate the victim or catch them out for things like outstanding warrants or fines, bald tyres, or unregistered vehicles.

These stations resemble barrio houses. They are colourful, welcoming spaces, with designated areas for children and pint-sized tables and chairs. All of them provide childcare, and emergency supplies, such as provisions of clothing and other items, for women and their children who have left a violent partner.

Female police officers are the staffing majority within these stations, and a few good men who choose to complete the required training. All are highly skilled in responding to gender violence with empathy, giving victims the security to share their experiences and protection from their perpetrators.

It’s a multi-disciplinary approach. Teamwork is essential. Police work alongside a team of social workers, lawyers, psychologists, and counsellors to ensure victims receive guidance, help, and support.

A civilian, a trauma-informed counsellor, is the first to welcome women to the station. They determine whether the person seeking help wants police involvement. It’s a victim-centric strategy, designed to put at ease women who fear the police, who don’t want to talk to the police, or who need time to become calm and settled before speaking to police.

Police are vetted from criminalising victims seeking help. They don't investigate the victim or catch them out for things like outstanding warrants or fines, bald tyres, or unregistered vehicles.

They don’t deal with any other matter except the domestic or sexual violence, which is why women trust the police enough to go to them in the barrios, as they know those police are prohibited from investigating anything else. They cannot be locked up just for seeking help. Limiting their power does limit these specialist police, but it significantly enhances their legitimacy.

And yet, it wasn’t always this way, not by a very long shot.

Welcome to Argentina's 'Dirty War.'

The Catalyst

1976-1983

Argentina is in the horrifying grip of the ‘Dirty War.’ The country is ruled by the military junta, who have forcefully seized power from the democratically elected government and kidnapped thousands of their own people who they suspect of rebellion.

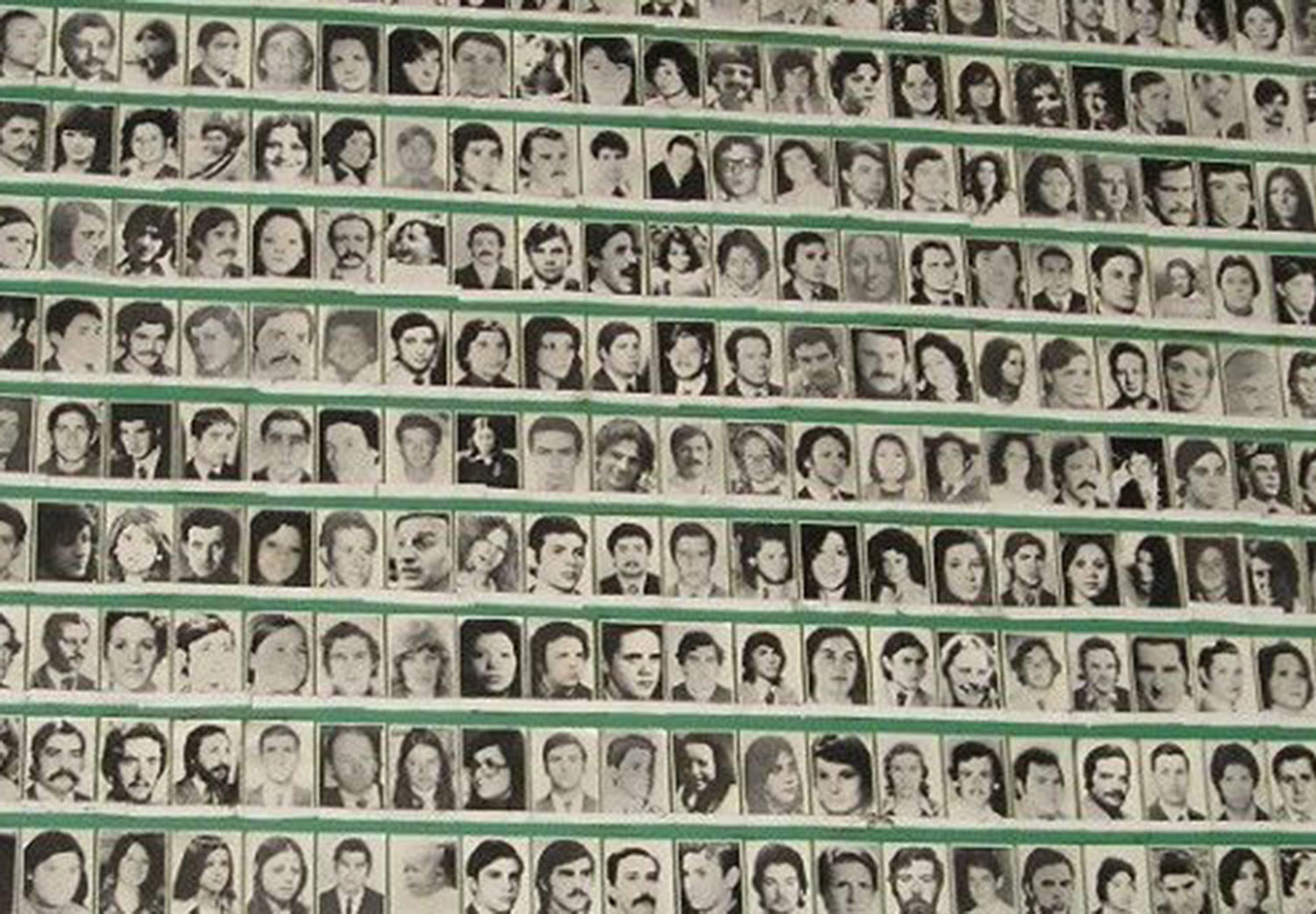

Tens of thousands have disappeared, up to 30,000 people. ‘Los desaparecido’ – the disappeared – are mostly young students and activists, many of whom are women. They are dissidents, free thinkers, liberals. A generation of artists, teachers, journalists, academics, and unionists.

They are abducted, raped, tortured, and murdered. There are no records of their arrests, no evidence of their alleged crimes or the charges laid against them, and no proof of their deaths. They have vanished without a trace, never to be seen or heard from again.

But the mothers, and the grandmothers. The military junta did not plan for them. They discounted the power of a mother’s love, and the strength of her anger.

Babies, too, are stolen. Approximately 500 of them, taken from their mothers who were pregnant when they were arrested, or who became pregnant through rape while incarcerated. These stolen infants are given to military and church families, to be raised as their own.

Those responsible are soldiers, police officers and military-backed militias who ruthlessly enforce a patriarchal campaign of violence, of severe repression against suspected political opponents. No corner of the country is left untouched.

But the mothers, and the grandmothers. The military junta did not plan for them. They discounted the power of a mother’s love, and the strength of her anger.

It’s the women, ‘los Abuelas y Madres de desaparecido,’ the grandmothers and mothers of the disappeared, who refuse to let them disappear silently.

It begins with just a handful of 14 women, who decide to act, despite the overwhelming peril. The law criminalises assembling in groups of three or more, which they circumvent by marching in pairs. They stand at the gates of the presidential palace, carrying placards with the faces of their missing children and the dates they disappeared.

14 incredibly courageous women soon become hundreds. They become known as ‘Los Madres de Plaza de Mayo’. They march, demanding answers. They are not deterred when five of the women – three of the founding members and two nuns who are sympathetic to their cause – are abducted and murdered. Still, they will not go away.

The government cannot get rid of them, and so, they attempt to discredit them. They are called mad women, ‘las locas.’ And indeed, they are mad, mad with grief, with anger.

Their mad courage and determination to march every Thursday, for decades, reminds the world, over and over again, what their government has done, who have they have silenced.

Then, it’s 1983, and a democratically elected government at last replaces the domination of the despotic military dictatorship. It’s largely thanks to the perseverance of the mothers and grandmothers, and other civic groups, whose protests are the catalyst that shifts the balance of power.

And yet. How can trust be restored?

It was the soldiers. The militia. The police, the men in power responsible for the crimes of kidnapping, rape, torture, and murder.

So. When those committing the crimes are the ones meant to protect and serve. When the perpetrators of injustice are meant to prevent it, how can trust in government, in police, ever truly be restored?

In short, by creating a new government, and a completely new police force. One that could be trusted.

And that is what they did.

The Researcher

From the first time Dr Kerry Carrington visited a female-led specialist police station in Argentina in 2015, she was hooked into wanting to know more.

“I'd heard that one of these women-led police stations existed in Santa Fe, Argentina, so I convinced one of the lecturing staff at the university there to ask permission for me to go and see it,” Kerry says.

“That was it. I could not believe what I saw, what I heard. I thought, that’s it, I need to raise the money to come and do a study.”

Raising the money for a study took three years, and in that time, Kerry began the daunting task of getting permission from the right authorities in Argentina.

“The first time I went to the Ministry of Security, I was told I would not get permission, as they'd never let any outsider into one of these stations, let alone to research it. The second time they said, ‘Well, maybe.’ By the third visit, I'd secured funding from the Australian Research Council to put together a research team, so I was like ‘You have to let me, I have the money this time!’”

“The fact that the Australian government committed money to studying their policing model really surprised them. They said, ‘You won a research award to study what we do?? You must be the first person outside of Latin America who has done this.’”

Kerry’s perseverance paid off, with her research team becoming the first to get formal approval to study female-led policing units run by the Comisaría de la Mujer y la Familia in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The team was made up of researchers from three universities in Australia and Argentina, and was led by Professor Kerry Carrington and Professor Máximo Sozzo from Argentina’s Universidad Nacional de Litoral.

Everything the research team wrote was translated from English into Spanish and handed over to the Argentinian authorities, but Kerry says they were never vetted, censored, or stopped from publishing anything. “We published what we discovered, including criticisms,” she says.

Their study, titled ‘Preventing Gendered Violence: Lessons from the Global South’ and its subsequent findings have been published widely. Kerry continues to use their findings from the study to advocate for the advantages of women-led police stations, which she believes could significantly improve the Australian response to gender violence.

On the 21st of March, 2019, Kerry and her fellow researcher María presented their findings to the United Nations 63rd Commission on the Status of Women, NGO Sessions in New York.

Recently, Kerry used the findings in her submission to the Independent Commission of Inquiry into Queensland Police Service responses to domestic and family violence, after multiple submissions from victims outlined alleged police failures in their response to domestic violence.

The Change

While not an overnight change, by 1988, Argentina had created a brand-new police force they called ‘Comisaries de la Mujer,’ which later became ‘Comisaries de la Mujer y Familia.’

“No one could trust the police, so they created a completely new police force and set up the first female-led police station to tackle the problem of domestic and gender violence,” Kerry says. “From 1988 to 2004, those stations were run by women only and women-led. You had to be a woman to work in them.”

In 2004, men were given the opportunity to work in specialist police stations after they received the required training.

“TRAINING is the significant entry point into this police force,” Kerry says. “Officers have specific training on how to respond to domestic violence. Working from a gender perspective, is a compulsory part of their training.”

For the 10% of men who choose to work in this career pathway, it is often born of a passionate desire to end the cycle of violence.

"The men who choose to do this are committed, and also incredibly proud of the path they have chosen, they view it as a great honour to do this work and they want to be there."

“One of the male officers we interviewed said he was a child survivor, that his mother had been a victim of domestic violence, and it was this specialist police unit that had saved his mother, and their lives,” Kerry says.“He said, ‘My mother and I wouldn't be here if not for them, so as soon as I grew up, I immediately joined the specialist force and dedicated my entire life to this service.' There are lots of stories like that.

"The men who choose to do this are committed, and also incredibly proud of the path they have chosen, they view it as a great honour to do this work and they want to be there."

Another male officer interviewed by the research team, said he'd been a commander in the normal police for many years, and he saw an opportunity to up-skill and get a promotion by specialising in the family and domestic violence unit. It’s now seen as a promotion within the common police, to get into the special police.”

Critics of this model say it leads to this idea that women in policing can only do these lesser, specific tasks, not ‘real’ policing. An argument which, Kerry says, is a “really anglo-centric way of seeing it.”

“In Argentina, it’s the reverse! It’s not seen as an inferior task, it's seen as a real honour. It actually assists your career in the common police.

“It also supplies a career in policing and security that these women would otherwise never have chosen to have. They are paid the same and given the same ranking as men, something that was denied to women previously.

“To say this work is less important, relegates domestic and family violence to the ‘It’s a private matter, not a public matter, not real police work,’ which is a fundamental problem with the police response to gender violence, that deeply ingrained cultural problem particularly within the older ranks of the police. ‘Domestic violence isn’t really a crime, we shouldn’t be dealing with it.’ There are these kinds of stigmas attached to it that are very backward.”

“So now in Argentina, 41% of all police are female, the highest percentage in the entire world. Compare this to Australia which is around 28%, and we don’t have many women placed in hierarchal positions of command. The UK has 30%, while the USA and many other English-speaking countries have nowhere near that.”

However, Kerry insists that simply adding women to the existing police force does not solve the problem.

“You’ve got to change the structure. For women to succeed within the current structure, they have to take on a lot of these values to compete with the men. Research shows that just adding women does not solve the problem, you need to create a different solution. This is creating a different solution.

Not all officers are a good fit to deal with domestic and family violence, so Kerry says this is a win-win because it creates a structure where people can choose to police gender violence.

“After having these in place since 1988 in Argentina, the effect it has had on the policing culture has been phenomenal, even if it’s taken them a generation to get there."

Kerry says a key component of this model's success is to create a command structure separate from the rest of the police, protected by a strong commissioner, with a reporting structure to dual ministers, as in Argentina where specialist police report to the minister for women and social development as well as the minister for security. “Having dual reporting lines means they are protected and not ‘white anted,” Kerry says.

Another key is training for police, that is not delivered by the police. "Here’s where universities play a role in providing independently accredited, high-quality education and training,” she says.

Not all officers are a good fit to deal with domestic and family violence, so Kerry says this is a win-win because it creates a structure where people can choose to police gender violence.

"Right now, there is no choice. We have a structure where anyone who gets in to policing, finds that a third of their time is taken up by policing domestic violence, and they resent it.

“This encourages those who have specialised training and who want to police gender violence, to do this. Then they are rewarded, supported, and they stay in the service. There are people who would never put their hand up to be police, who would choose to specialise. Like the officer who said, ‘I saw my mother being bashed, I want to save lives, I want to be part of the solution.’

Kerry believes this model would also attract a much more diverse cohort to policing, including those from refugee backgrounds, culturally and linguistically diverse, and Indigenous Peoples.

“If you’re Indigenous, often the last place you want to work is the police, because of the history,” Kerry says. “But if you had the choice to work in an Indigenous-led specialist police station that focused on family and domestic violence, and the broader issues, you might say, ‘I want to be part of that solution, not part of the solution that locks people up. I don’t want to be part of the general police, but I do want to be part of this.’”

The Bold and the Butterflies

Back to the bold, bright, colourful murals painted across the entrances to specialist police stations in Argentina. The murals are there to challenge the norms of domestic violence as something that should be kept hidden, that there is shame attached to the survivor.

“Instead of hiding the fact, it says, ‘Break the silence, ditch the shame, because it’s not yours, it’s the perpetrators!'" Kerry says. "It also says, ‘Come to us!’ They are loud and ‘out there’ for the very reasons of challenging the ideas that privatise the trauma of domestic violence, instead of making it an individual woman’s problem.”

"They don’t blame men as a group, they call it ‘machismo culture,’ but they note if all this has been learnt, it can therefore be unlearnt.”

These socially advanced ideas can be credited to the end of Argentina's military dictatorship, when the culture of ‘machismo’ was challenged.

“The new government said, ‘Men’s violence against women is not biological, it’s all social and environmental,’ and they established centres for men to be put in to unlearn their violence,” Kerry says. “This therapeutic understanding of gender violence means if you have learnt to be violent from ‘machismo culture,’ from your fathers, brothers, workmates, your pub or your culture, you can UNLEARN it. So it’s a very positive intervention.”

For specialist police units, the immediate intervention is to stop the violence, not necessarily to take criminal justice action.

“The preventative impact of these stations is that they encourage women to come forward much earlier in the cycle, and they send the violent partner away for training and to be ‘reconstructed.' Their therapists and counsellors are very sophisticated.

"They don’t blame men as a group, they call it ‘machismo culture,’ but they note if all this has been learnt, it can therefore be unlearnt.”

At least once a month, specialist police officers spend time on community outreach for the prevention of violence. They work with schools, community groups, religious organisations, women’s groups, and hospitals. They organise community campaigns on special holidays, and during protests against femicide.

At Christmastime, a time which often sees an increase in gender violence, officers dress as Santa’s helpers and drive around the neighbourhood with sirens blaring, handing out colourfully wrapped presents containing their contact details and information about domestic and sexual violence.

Could it work, in the Global North?

We tend towards arrogance in the belief that developing nations should learn from us, and not the other way around.

Some believe that English-speaking countries should only look to other English-speaking countries for guidance. Some say this model is too anglo-centric to work in Australia's Indigenous communities.

And yet, Kerry advocates for the fact that we, as a nation, are perhaps more similar in our history than we care to admit, and have much that could be carried across from the Latin American policing model.

“The relationship between First Nations people and the police is fraught, as they have historically been the instruments of colonisation and removal of children,” Kerry says.

“In Argentina, military police were instruments of torture and abduction, so of course no one would go to them to seek help for domestic violence. It’s exactly the reason why these specialist police stations were invented.”

About a third or more of Argentinian women are ‘mexcla,’ meaning they have some indigeneity. Many live in the barrios, on the outskirts of town, and are often in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Exactly where these specialist police stations were established. “It wasn’t white women, for white women. This response to domestic violence was mainly invented by women of colour,” Kerry says.

“My research team has also done two surveys in Australia, one with the domestic family violence sector which included government and policy workers, police, social workers, etc., as well as a community survey which asked, ‘Do you think these specialist stations would work in Indigenous communities? And if so, under what conditions?’

“Nearly everyone agreed they would work, but they would have to be Indigenous led, and involve a mix of genders because of factors like secret women’s business. Indigenous women would lead these centres, but Indigenous men would have a big role to play with the perpetrator program.

“Unlike now, law enforcement would be the last option – not the first option. In many cases, women do not want their partner to go to jail or to be removed, they want reconciliation."

Indigenous Peoples, says Kerry, are currently the most disadvantaged in the way we deal with domestic violence in this country. And to put an Indigenous man into custody as the first option adds layers of disadvantage, because he may be the primary breadwinner.

Kerry insists the proposed model is not about funding more police for Indigenous communities. If it was done properly, it would be led and performed by Indigenous police in collaboration with non-Indigenous professionals, such as lawyers and social workers. A multi-disciplinary approach, though always Indigenous led.

Not one more

Women’s specialist police stations began in Brazil in 1985, with Argentina next to follow suit in 1988. The concept grew slowly at first, but by the time Kerry and her team conducted their research project in 2018, there were 128 women’s police stations in Argentina employing approximately 2,300 officers and multi-disciplinary teams of lawyers, social workers and psychologists, who responded to around 245,437 reports of domestic violence.

Thousands of women’s police stations have now been established across the world—in Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Peru, Uruguay, Sierra Leone, India, Ghana, Kosovo, Liberia, the Philippines, South Africa and Uganda.

Could Australia be next to follow suit? There are hopeful signs, including the coroner's recommendations into the deaths of Hannah Clarke and her three children, handed down in July 2022, which made very detailed recommendations about a specialist police station, recommendations which Kerry hopes will be the catalyst for change.

“Domestic violence is all about gender inequality,” Kerry says. “If you don’t understand gender, you cannot understand the cycle of violence. To respond to it, to prevent it, you have to understand the link between power and gender, and, as a law enforcement officer you must understand it’s a cycle.

"So, it makes complete sense that you have to police it very differently, certainly to other types of crimes.”

Media enquiries: Please contact the Media Team media@usc.edu.au