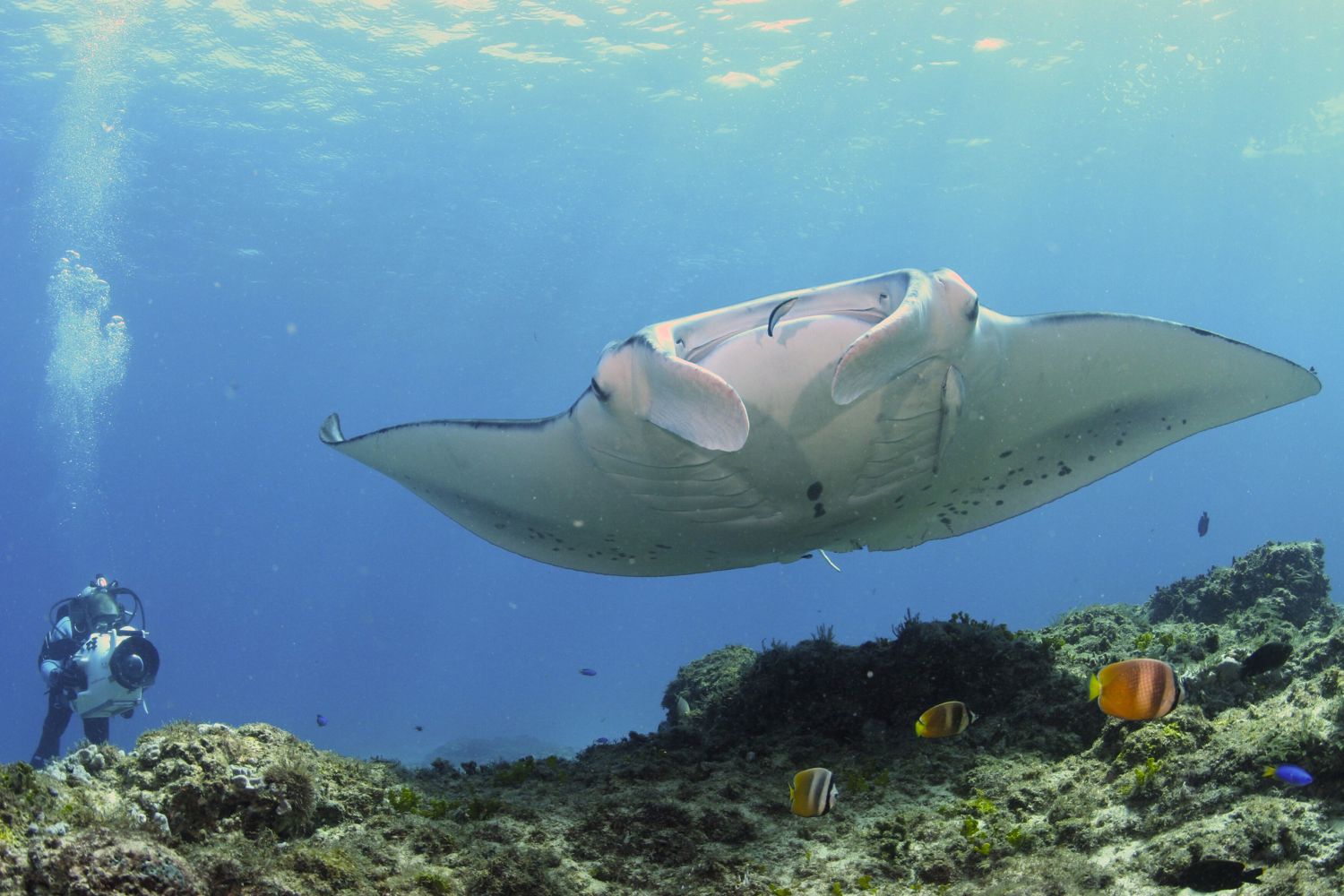

In the deep blue waters of the Maldives, University of the Sunshine Coast PHD candidate Hannah Moloney is free diving in the middle of a swirling vortex of manta rays – searching for answers to a rare feeding phenomenon.

Up to 150 manta rays – many the size of small cars – are head to tail, following each other in a chaotic loop, creating an underwater feeding ‘cyclone’ in a frenzied hunt for zooplankton.

Hannah is part of a team of UniSC researchers collaborating with colleagues around the world in an urgent global search for insights into these vulnerable ocean giants.

“Manta rays are key indicators of a changing climate and the more we learn about their feeding and behaviours, the better we can understand how they will react to climate change, habitat disappearance and other threats.” - Hannah Moloney

The research is combining findings on mass feeding events at Hanifaru Bay in the Maldives – host to the world’s largest aggregation of manta rays – and in southern Queensland, including a newly discovered site off the tip of World Heritage-listed sand island K’gari.

Their small but important food source, zooplankton, is extremely sensitive to changes in its environment.

“A changing climate threatens to decrease zooplankton biomass by up to 50 percent in some tropical regions, which will affect the availability of food for manta rays and other species who rely on it,” Hannah said.

“With the dark cloud of climate change and the intensity of systems such as El Niño and La Niña looming above us, it is more important than ever to understand what drives these natural systems.”

Working together to reveal manta mysteries

The project is supported by Project Manta, a multidisciplinary research collaboration based at UniSC, focusing on manta rays within Australian waters, and at key global sites such as the Maldives, Mexico and Micronesia.

Project Manta’s lead academic, UniSC Associate Professor Kathy Townsend said that with manta ray populations around the world also decreasing because of human-impacts, there was a race to understand how to protect them so they can thrive into the future.

“Studying manta rays across international borders is important as each population is facing a unique set of human impacts and will react to changes in the environment differently,” Dr Townsend said.

“Despite years of research, manta rays remain a mystery and it is hoped our findings will inform management policy and practice to protect individuals and safeguard populations. This is especially relevant to Australia, as we are not fully aware of all major feeding grounds or where the manta rays go to mate and give birth.” - Associate Professor Kathy Townsend

Feasting giants, somersaults, piggy backs and chain gangs...

Throw in 'cyclones' to the above list of strange, acrobatic maneuvers and you have some of the eight strategies that scientists have identified manta rays use to funnel plankton-rich water through their specially adapted gills.

This creative, complex, and cooperative foraging could be key to their feeding success.

But major knowledge gaps remain and Hanifaru Bay, a UNESCO biosphere reserve in the north-central Indian Ocean, presents the ideal location to find important answers.

“Hanifaru Bay is an unsuspecting small reef inlet the size of a football pitch and when the perfect recipe of prevailing winds, currents, tides and moon phase occurs, it becomes a key site for large megafauna to feast on tiny nutrient-rich zooplankton,” Hannah said.

“These manta rays are faced with the zooplankton dissipating into the deeper waters at any moment, so they race around scooping up as much as possible with their unfurled cephalic fins and mouths wide open while this ephemeral hotspot lasts.”

“Surreal and magical”

Since her first encounter with these graceful, intelligent creatures (they have the largest body to brain ratio of all “fish) on a dive in the Maldives in 2015 – Hannah has been under their spell.

“Despite all the fabulous things about mantas, they are a threatened species with populations declining globally. I guess their vulnerabilities alongside their charisma has captured my attention.”

“I love their curiosity towards divers and snorkelers.

“Sometimes hungry mantas will zoom past snorkelers in the water while on the hunt for food, or they’ll linger over the top of scuba divers waiting for their exhale to create a bubble-bath which must cause some interesting sensations for the mantas.”

She lists many incredible experiences with the gentle sea giants but there is one that stands out.

“It was surreal,” she said.

“In the Maldives and many other locations, it is common for manta rays to get hooked and entangled in fishing line and one day in Hanifaru Bay, we encountered a manta named Sponge Cake, who had it around her cephalic lobe (face fins to help with feeding) and a massive trailing line.

“If it was to remain on her cephalic fin, it would likely amputate it in the future, hindering her foraging abilities. However, Spongecake didn’t make it easy for us.

“She joined the other mantas in “cyclone” feeding and was surrounded by 30 other manta rays feeding vortex that reached 20 metres across and 15 metres to the seafloor.

“Armed only with a small dive knife, big fins and a good breath hold, we free dove down beside the cyclone of manta rays waiting patiently to get close to Sponge Cake."

“With the help of my colleague Cat, we managed to cut off the trailing line when she passed underneath us, then we endured to cut the line that was strangling her cephalic fin."

Media enquiries: Please contact the Media Team media@usc.edu.au